Shay Salehi

July 4, 2025

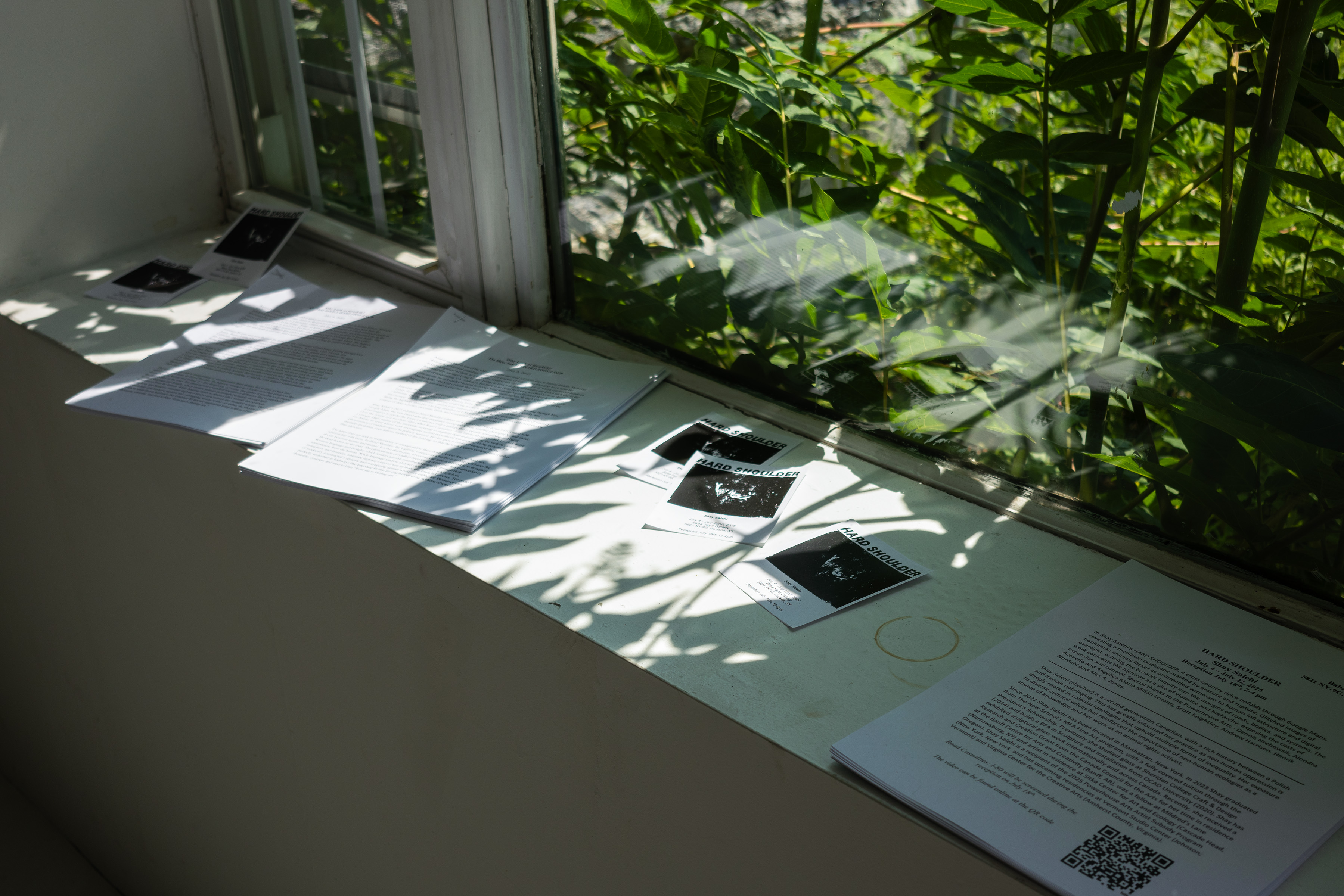

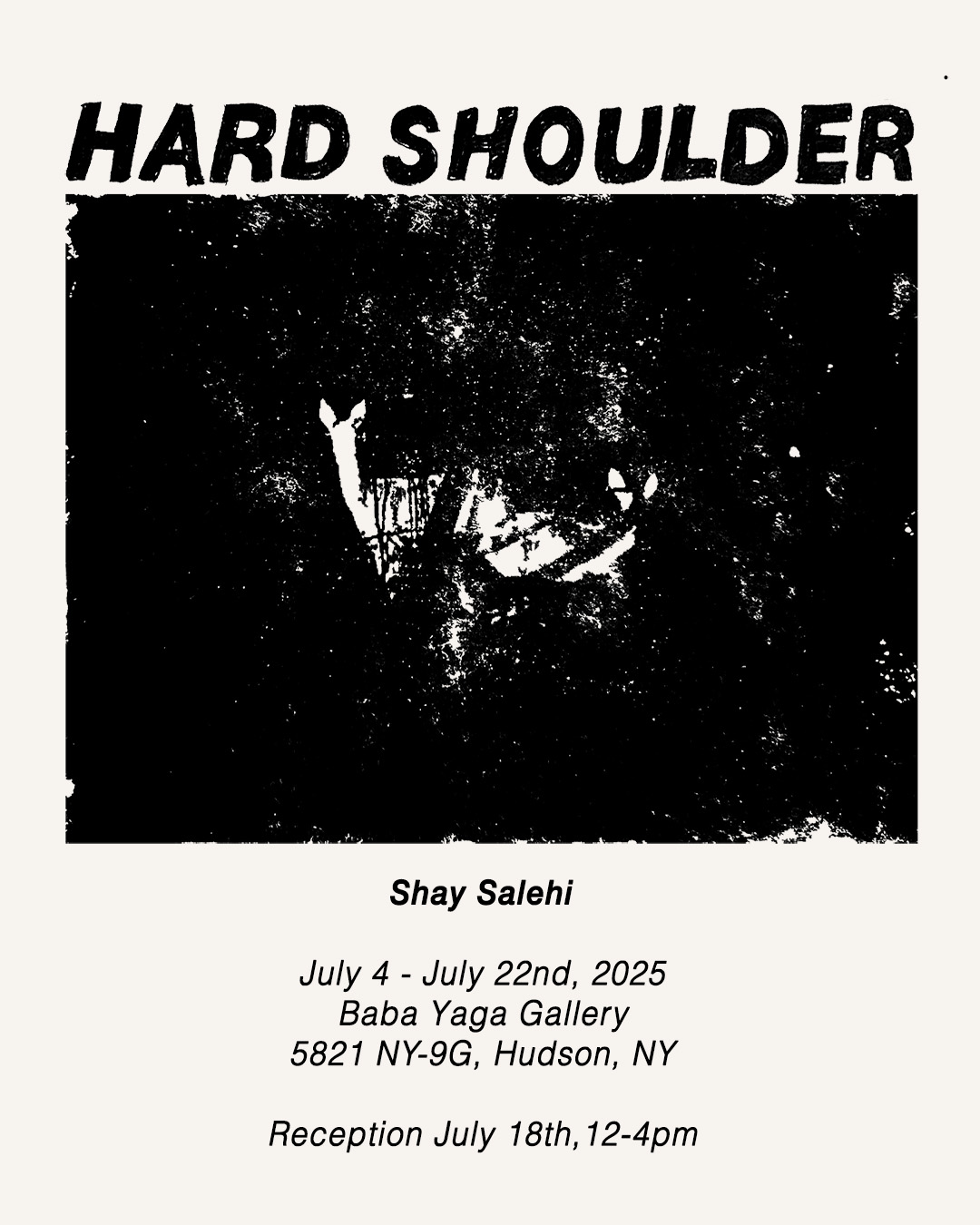

In Shay Salehi's HARD SHOULDER, a cross-country drive unfolds through Google Maps, revealing a mediated landscape marked by erasure and rupture. Glitched images of nonhuman animals flicker as unintended witnesses to human infrastructure and digital oversight, echoing the broader inquiry into the margins of roads, bodies, and systems. The work confronts the highway as a site of violence and hierarchy, exposing the costs of expansion and control.

Why Look at Roadkill?

On Shay Salehi’s Hard Shoulder

Alex A. Jones

Animal sacrifice is one of the oldest and most universal religious rites in human history. However diverse its existential meanings, innate to the practice of animal sacrifice may have been the acknowledgement of death as a necessary creative act, the ritualization of which reinforced bonds of accountability amongst living beings. Today, at least a million vertebrates are killed each day in the course of perpetuating U.S. roadways, but there is no ritual reverence ascribed to these deaths. The phenomenon we call roadkill instead embodies what anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose called “double death,” the kind of death that renders mortality meaningless,

Interstate 80 runs east-west through the middle of the continental United States, passing through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California. The embodied experience of driving across it, at cruising speeds that compress the land into scenery, can be cinematic—unless your immersion is broken by the grotesque amount of roadkill lining the highway shoulder. On long stretches of I-80 it is difficult to drive ten seconds between the corpses of deer, coyotes, raccoons, birds, and sometimes- indistinguishable species.

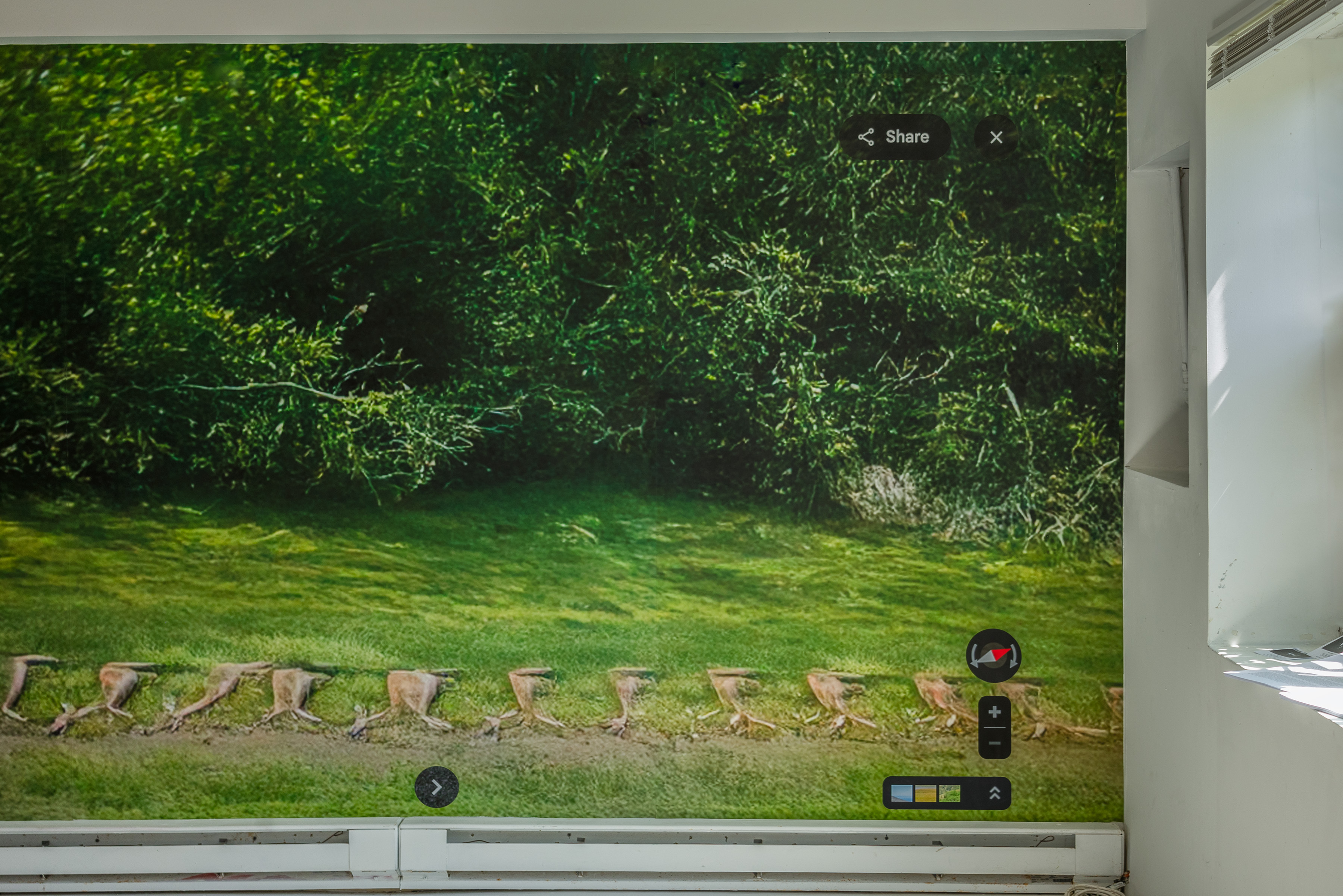

Shay Salehi’s 2025 exhibition Hard Shoulder centers on a virtual road trip down I-80 created with Google Maps, the web-based atlas that integrates cartographic data, satellite photography, and street-level imagery to render the Earth’s roadways with a totality that is equally astonishing and banal. Over the course of a two-hour film called Road Casualties: I-80, Salehi advances click-by-click down a Google Maps replica of the interstate, stopping to examine dead animals using the built-in camera. For Salehi, an artist whose work investigates animal personhood and uncanny living systems, the phenomenon of roadkill cannot be politely ignored. But her gaze is rendered impassive by the digitally-mediated, even tedious method of her looking, so that the work triggers contemplation rather than abjection.

The artist does not seek to memorialize or sensationalize these deaths, but to draw us back into relationship with them. In Hard Shoulder, the highway emerges as a border-zone that reinforces the divide between human and animal. It’s this distinction, of course, that makes it possible to disregard the dead bodies on the road. The phenomenon of roadkill literalizes a difference that is preceded in Western language and thought, which renders animals meaningful primarily through their separateness from the human. While language tends to abstract other animals into symbols, metaphors, and fantasies, interstate highways tend to turn animals into mangled corpses. The project of modernity constructed a separate and overlapping human world—or rather, the illusion

through which “the balance between life and death is over-run, and a relentless cascade is piling

up corpses in the land of the living.”

of one, perfectly embodied in highways like Interstate 80 that are engineered using millions of tons of dynamite, concrete, and steel to blast “from sea to shining sea.”

Salehi’s use of Google Maps links the technological flattening of reality to the loss of land-based and multispecies ecologies. Google Maps is a direct descendent of the interstate highway system, digitizing its logic of abstraction (and extraction) that upholds human utility, mobility, and standardization as driving values. The digital map is a streamlining interface that continually overwrites old data, just as I-80 is an “update” of older roads. The current freeway sits atop the Lincoln Highway, the first automobile road to cross the continental U.S. in the early 20th century, which was itself re-configured from sections of the Lancaster Turnpike (the first paved highway in the country), the Overland Trail (an important route for stagecoaches in the 19th century), and multiple ancient Native American trails. The latter of these were often the same footpaths made by large animals like deer and buffalo, elder species whose knowledge of sensible overland routes extends millennia into the past.

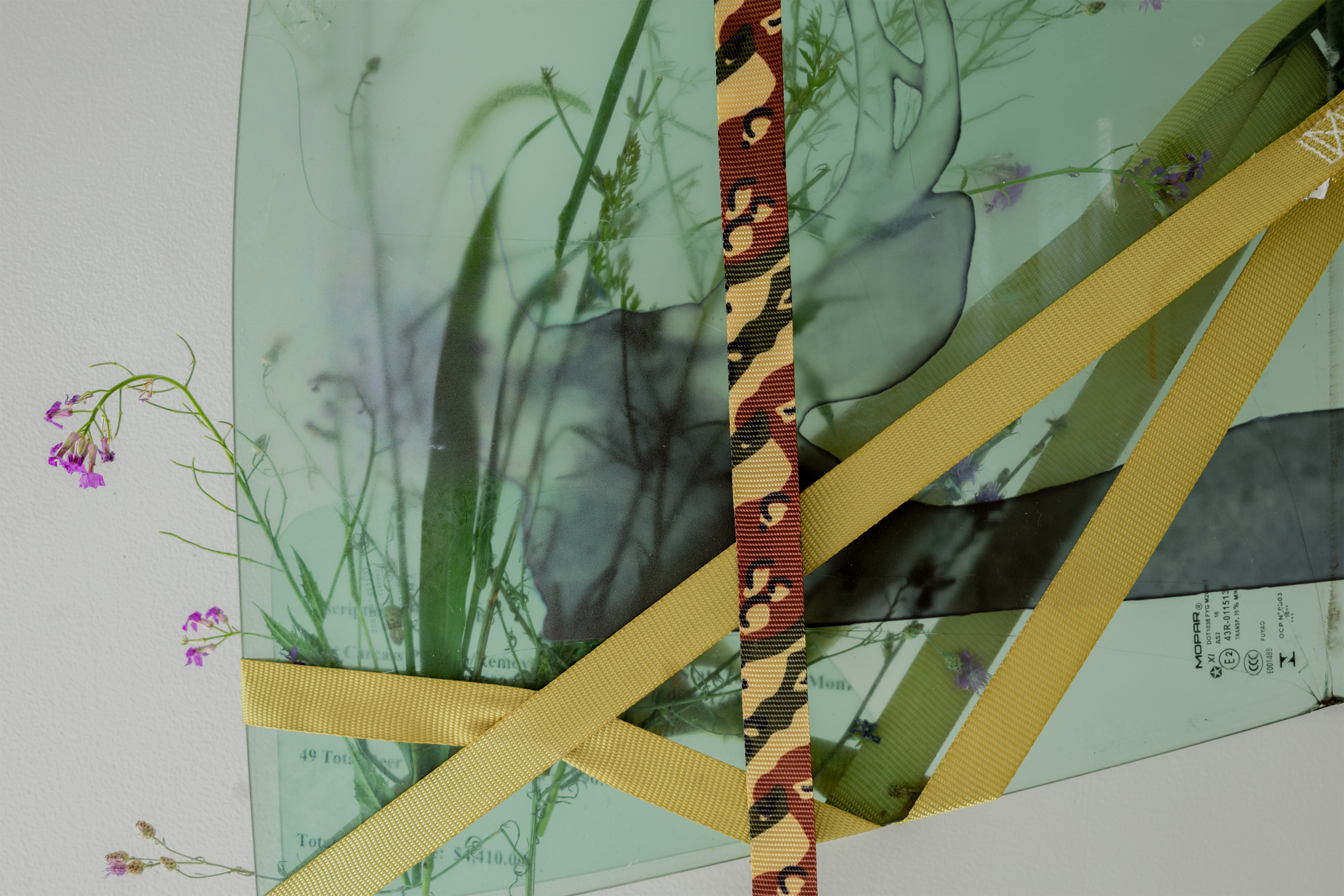

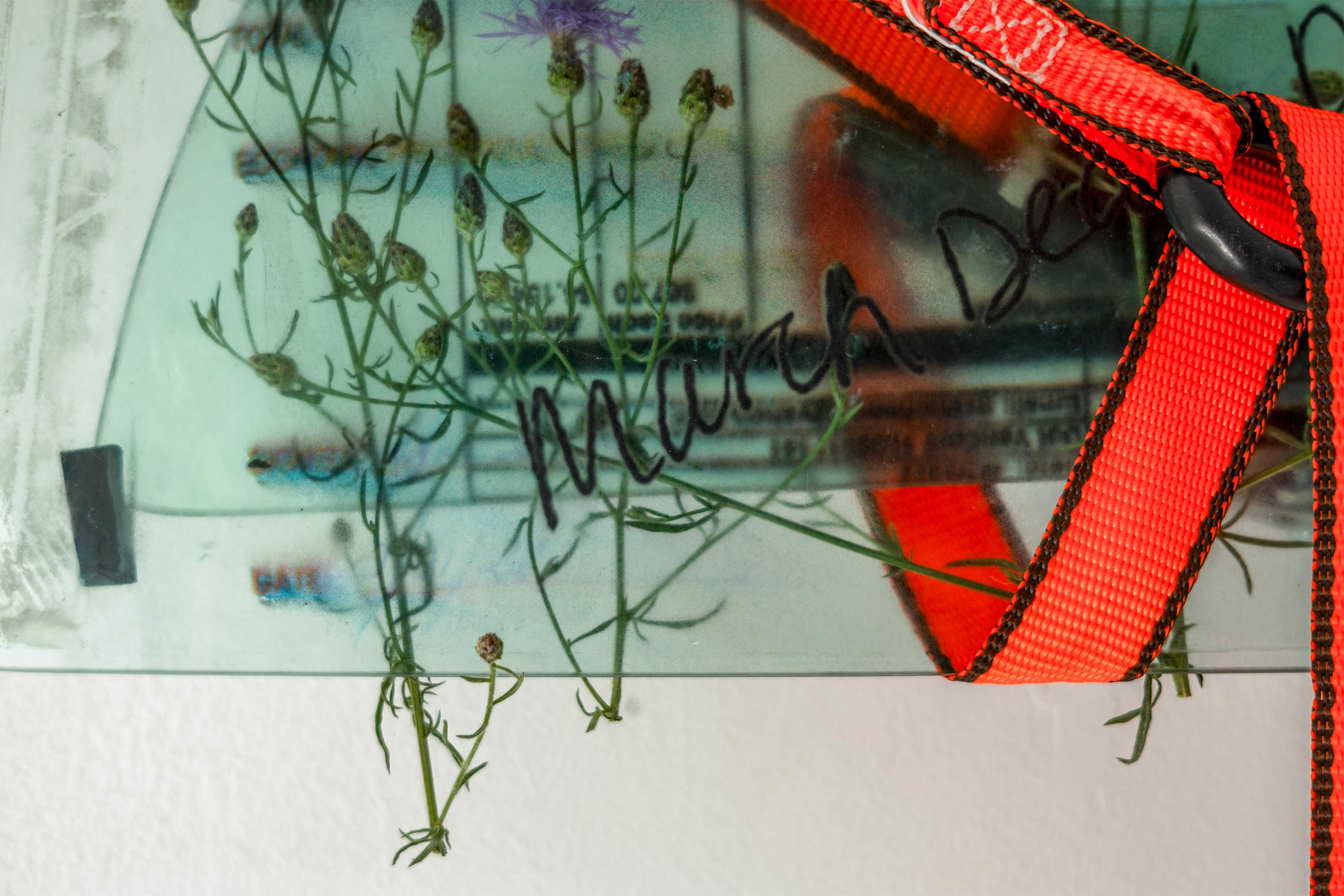

The modern infrastructure of colonialism and petro-capitalism is designed to erase the presence of other animals, but often fails to do so. Roadkill—whether on the highway itself or its archive in Google Maps—is an accidental trace of estranged ecologies. In Hard Shoulder, Salehi’s artistic gaze lingers on uncanny specimens distorted by the stitching of images in Google’s artificial experience of the road. One is an unfortunate deer depicted in the panoramic print, Ghost Index, whose dead body has been repeatedly stamped on the roadside by a glitch in the software. The fact of the deer’s death is doubled, tripled, multiplied dozens of times; like the stutter of a skipping record, it’s an accident that reverberates.

Salehi’s representations of dead animals are made tolerable to witness by the abstraction of the glitchy, low-resolution imagery. She holds us at a distance—in time, space, and detail—from the corporeality (the corpse-reality) of these deaths. She keeps them comfortably virtual, but insists that they are existential imprints of something real, drawing us deeper into a dialectic of disembodiment and rematerialization. Virtuality is the dislocation from embodiment that alters our perception of what is real, and it’s become an important aesthetic domain for fracturing and opening space in our ontologies. But virtuality also severs us from material worlds, often delivering us to dead-ends of abstraction.

Google Maps has shifted millions of users’ experience of space, place and movement, normalizing a satellite view of the planet derived from technologies of occupation and surveillance. Earlier in the 20th century, the development of interstate travel also offered a new, virtualized experience of the land, turning cross-country travel into a sort of personal cinema for the driver, one which could eventually be set to one’s own soundtrack. (Now with air conditioning!)

Salehi’s video-sculpture You Look, I Look literalizes an automotive cinema. A rear-view mirror hangs in the gallery, and within its frame plays a nighttime video of a deer standing in the road, lit by headlights. One’s own reflection ghosts in the image of the deer as it looks into the camera. Dangling under the car mirror are a pair of stainless-steel “pine tree” air fresheners, one of the ultimate signifiers of the modern automobile lifestyle, and an object designed to enhance the private environment of the car. These mock air-fresheners are etched with a quote by John Berger:

The animal scrutinizes him across an abyss of non-comprehension, and the man too is looking across a similar, but not identical, abyss of non-comprehension.

The line comes from an immensely influential 1980 essay called “Why Look at Animals?” Often cited as a precursor to the contemporary field of animal studies, this piece makes a moving elegy for the disappearance of the animal from modern human life and its regression into token roles of pet, specimen, toy, and image. Berger makes critical observations about the ways animals are commodified, anthropomorphized, and ultimately dematerialized. But his essay is also quintessentially modern, emphasizing at every juncture the fundamental separateness of man and animal. As encapsulated in the quote above, he casts the animal as a timeless other, a mirror in which man has seen himself and his own symbolic order.

There’s a knowing irony in Salehi’s You Look, I Look, which literally tokenizes Berger’s famous text. Her assemblage presents a fragmented and spectral view of the animal, but one which implicates the humanist constructs that separate us from animality—the car, the camera, the conceptual binary. Paired with the imagery of Road Casualties, there’s a darker irony as well; whatever romantic abyss may be cast between man and animal, it reaches an event horizon in the sudden impact of steel on flesh. “Everywhere animals disappear,” John Berger eulogized, but roadkill resists the notion of absence. On the side of the highway, animals do not disappear — they reappear with overwhelming regularity, not as specters or metaphors, but as real bodies: broken and undeniable. Each collision is not a symbolic erasure, but a violently embodied encounter.

The affective power of Hard Shoulder is a call toward corporeality, presented through the broken mirror of the virtual. Salehi’s work reflects a still-emerging wave of multispecies ethics that aims to dismantle the animal/human binary, restoring the basis of subjectivity and kinship to what Anat Pick calls “shared bodily vulnerability.” In our shared condition of embodiment lies the cure to what Berger described as humankind’s “species loneliness,” and also the route by which humanity’s cascading ecological disturbances will eventually come circling back to us. “In life and death,” Robin Rose Bennett counters, “we are never alone, either as individuals or as a species.”

To look at roadkill is to face double death. This is the harrowing meditation Salehi undertakes in Road Casualties. Her deathwork is mediated by virtuality, not only to shield herself (and us) from a horror that is otherwise unbearable, but to withhold any idealistic appeal. If a dead deer is not seen sentimentally as a symbol, moralistically as a victim, or solipsistically as a mirror—but is instead understood as an index of broken life cycles, then there may yet be room for ourselves in that web of relations as something more than an estranged observer. The first step toward an ethics of proximity and consequence is a simple act of attention.